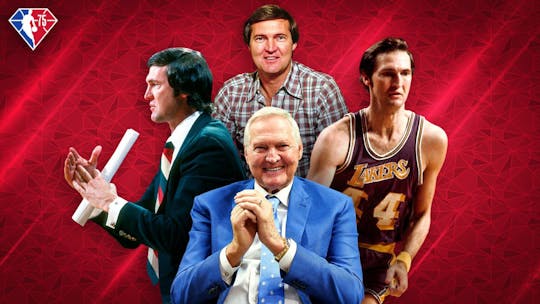

LOS ANGELES — He is 83, the oldest guy in most rooms he enters these days and most definitely the coolest. He still has his hair, his LA looks, his aura and his way of making and leaving a lasting impression on those he meets for the first time or the umpteenth.

His typical greeting is, “Great to meet you, I’m Jerry West” just in case the one unaware soul on the basketball planet doesn’t have a clue. West has learned never to take anything for granted anymore, though, especially at this age, where he often wonders if anyone still remembers or cares.

“When people come up to me, I’m shocked,” he says. “When someone wants to talk, I always say hello. When someone asks for an autograph, I sign. I’m just happy and blessed they recognize me.”

He is sensitive in that way, and others. Imagine this: No other person has managed to match his multiple layers of success in the NBA and yet what’s peculiar about West is how, despite this mountain of compelling evidence, he still craves the love and respect of those whose love and respect he has more than earned.

That craving is what made him pick up a basketball in small-town West Virginia as a lonely kid with an uncaring father and begin the dream. That craving made him legendary on the NBA floor and inside the front office. That craving has kept him in the league for 60 mostly uninterrupted years — nobody ever cashed NBA paychecks over a longer period of time — and encourages him to stick around, as a consultant with the Clippers.

Without that craving, there are no Jerry West Hall of Fame moments, no iconic silhouette logo tattooed on all things NBA, maybe no decades of big box-office basketball in L.A., no Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant, no reason for the Laker Girls to shake and wiggle … shall we go on?

Yes, love and respect, the ultimate concoction. He would like that from the Lakers, the franchise he helped polish and glamorize, but theirs is a frosty relationship without thaw. He would like that from the game itself, which he popularized in the 1960s at the highest level, the game that should name the NBA Executive of the Year Award for him after all those laps he ran around his peers, but then West was taken aback by what he heard recently.

One of his sons relayed a message plucked from the NBA grapevine, or maybe it was from social media — doesn’t really matter which — that said, in part: Jerry West is too old to know basketball anymore.

As he revealed this knife wound, his voice lowered and he admitted softly: “That hurt.”

And: “That really hurt.”

And then, after a moment’s reflection: “Well, after 50-60 years, it’s not something I should let bother me, is it?”

Well, no, of course not.

But upon hearing that, you figure Jerry West’s lifelong dedication to basketball and his grip on the game just grew a little tighter. Because of course.

“I read a lot,” he explains, describing his preferred method of combating senior citizenship, “because it keeps your mind sharp. I’m curious about a lot of things, and that’s just another way I learn about people. And the things I’ve learned by being a player and executive helped me understand people even more.”

West never stops evolving, as a basketball executive and human being. He will not let advanced age do that to him, to confine him to a rocking chair and lullaby him to sleep, oblivious to the spin of the basketball and real worlds.

As the NBA celebrates its 75th Anniversary season, its longest-tenured employee remains sharp. There are no geographical or gender or geriatric boundaries for him. West connects with Steve Ballmer, the LA Clippers’ billionaire owner who saw West play back in the day, and also Clippers star Paul George, who didn’t. The generation gap between West and today’s league might be oceanic from an age standpoint but there is a bridge constructed by West that he crosses daily.

Nobody in the NBA is rooted quite like West. He played in the 1960s and ‘70s. He constructed teams in the ‘80s, ‘90s and 2000s. He served as a key adviser to the Golden State Warriors in the previous decade and the Clippers this decade. He is a one-time champion as a player and eight-time winner as an exec.

He was out of the league only twice: Following his retirement as a player, and between front-office jobs with the Memphis Grizzlies and Warriors. That was for a total of roughly four years. The first absence made him miserable. The second absence, he was initially relieved; weary from the rigors of the NBA, he worked in golf, a passion of his, as an ambassador for the Northern Trust tournament, which he enjoyed. Then he was miserable again.

“I could hear that basketball dribble,” he says.

Therefore: The evolution, and The Revolution, couldn’t go on without West, could it?

He has seen, from point-blank range, all the players, trends, cultural shifts, old money, new money, bounces and buzzer-beaters the NBA has had to offer. When he entered the league in 1960, the NBA was slowly moving away from being all-white and having all set shots. Just as important, the franchise that drafted him, the Lakers, were moving from Minneapolis to Los Angeles and in that sense the league would never be the same.

As a rookie, West — shy and country bumpkin — made a decision that would enhance the rest of his life. He requested a Black roommate. West didn’t grow up around Black people in Chelyan and nearby Cabin Creek, West Virginia. At that point, with the exception of the exceptional 1960 US Olympic Team of which he was a member, West never had a Black teammate, didn’t know any Black people, really. And what he heard about Black people as a boy who idolized Jim Brown (West wore No. 44 in honor of Brown, who wore 44 in college) wasn’t very complimentary.

His desire and foresight to learn coincided with the demographical shift of the sport. He was looking for that love and respect again, from a race that was foreign to him. So the Lakers assigned him Ray Felix, born and raised in New York City, who was the NBA’s first Black Rookie of the Year and second Black All-Star but by then a journeyman who had much to tell.

“I learned more about race by being around him, about things he saw growing up,” West says. “It was a different education for me. It affected my reading. I looked for books about all the incredible minority leaders, about Civil Rights, so that’s what I did after games.

“After he got to know me, we became friends. I was a rookie and wasn’t playing much, and he used to tell me not to worry. I saw some of my other teammates who got more minutes, who didn’t stay in shape, they were out drinking almost every night and it frustrated me. I said to him, ‘I’m serious about this.’ He would tell me then, ‘You’re going to be one of the greatest players who ever played.’ I laughed and said, ‘I don’t know about that.’ But it motivated me.”

His next roommate was the great Elgin Baylor until Baylor left the Lakers in 1971. Their close friendship remained.

West and Baylor were a salt and pepper 1-2 punch, white man and Black man side-by-side during the racially-sensitive ‘60s, neither threatened by the other’s success. They would’ve won at least two championships if not for Bill Russell. West measured his worth by wins and losses, so the championship dry spell tortured him until he won his one and only title in 1972.

Still, West was brilliant. His fundamentals, instincts and his calm in the clutch were all top-shelf. He practically invented the term “two-way player” because his excellence as a shooter and ambidextrous ball-handling skills were matched by his defensive tenacity and desire to guard the toughest opponent. (The NBA didn’t begin All-Defensive teams until he was 32 years old and beyond his prime and lost some quickness, yet he still earned five selections.)

He never had a bad season. The 14-time All-Star averaged 27 points per game in his career, led the league in scoring (1969-70) and assists (1971-72) once each. His buzzer-beating half-court shot in Game 3 of the 1970 NBA Finals that forced overtime remains a classic. He averaged 46.3 ppg in the division finals against Washington in 1965, still the highest scoring average in a playoff series.

Then there’s the ultimate honor: He made the 35th, 50th and now 75th Anniversary teams.

Although he played against greats, West isn’t one of those legends stuck in the past. In his case, that’s not possible. Since he stayed working in the game for decades beyond retirement, his perspective is much broader.

“The players today are better and one reason is because they have it so much better,” West says. “When we played you had a trainer who put ice on you and that was his job. Now you talk to these guys and it’s like talking to a doctor. We only had one assistant coach. When we traveled, we flew coach. Not like now. The money they make, the support staff they have, everything has changed, and for the better.

“I admire LeBron James. He’s one of those players (whose legacy will) live forever, and there are so many amazing players today: Kevin Durant, Stephen Curry, these players are so gifted and tremendous that they would be good in any era.”

He has great hopes for the game’s future, citing the work done by Toronto Raptors president Masai Ujiri in growing the sport in Africa and says this about that untapped continent:

“They’ve become exposed, and I think basketball is soccer’s rival right now for the most popular sport. People may not believe that, but it’s close.”

He’s wary about “Superteams” and what talent-stacking does for the league image: “If a top-five player leaves a team in free agency, there should be compensation to the team he left. I think it would help protect smaller markets. And the agents, not general managers, are running certain teams. Some have become too powerful.”

Before he became general manager of the Grizzlies and advisor to the Warriors — urging them not to trade Klay Thompson for Kevin Love was crucial — West famously steered the Lakers through an era unmatched by any team except the ‘60s Celtics.

It gave him an extra layer of credibility, matched and in some ways surpassed his playing career for greatness. It fulfilled him, frustrated him and in the end, turned him bitter.

He inherited Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Magic Johnson, and along with owner Jerry Buss, constructed the dynasty that gave you goose bumps — “Showtime” — which elevated the profile and bankability of the league in the ‘80s.

And then, after Magic retired, West convinced Buss to write a big check for O’Neal, then conned the Charlotte Hornets into trading Kobe Bryant for an aging Vlade Divac in 1996, then hired Phil Jackson as coach, and that gave birth to the three-peat.

The love and respect for West came in gushes. Generation of fans who never saw him play only knew of him as the best GM in the game, if not ever. Those were halcyon days … and then West was squeezed out in a power struggle with Jackson in 2000.

The disconnect between West and the Lakers is no secret among NBA circles. He had a strong relationship with Buss, less so with the late owner’s children. He bristled recently when Jeanie Buss, in an interview, cited the five most important Lakers ever and left West off the list.

To West, this was a breach. He won’t go into detail about the Laker situation … except:

“I didn’t start this, OK? It was like family to me. My son Ryan (a former Lakers scout now with the Detroit Pistons) had been there a long time, loved the Lakers, and they let him go. And it was because of me. I know that. Also, Jerry Buss promised me season tickets for life. For whatever reason, they took them away. And that was like the last straw. They said anytime I wanted to come to a game to let them know.”

West is not feeling the love and respect at the moment, so he pauses and his voice lowers.

“I would rather buy a ticket.”

But because the roots run deep, and the retired jersey hangs in the rafters, and the man’s statue is cemented to the ground in front of Staples Center, Jerry West cannot truly let go.

“I will always root for the Lakers,” he finally concedes, “if they’re not playing the Clippers.”

Kobe Bryant is gone. Elgin Baylor is gone. When those greats died recently, a piece of West went with them. He was deeply hurt by the loss of each: he practically raised Kobe and was forever attached to Baylor, his “brother” and roommate.

West is asked: When this happens, do you process your own mortality?

“Oh gosh, no,” he says. “The end? That never concerns me. I don’t know what the number is for me, but there’s a number out there. I’m just hopeful I can continue enjoying life and stay in the game. I still have desire, still like to watch things come together, still like the spirit of competition. There’s something about this game that changed me forever, from the time I was a little kid, growing up the way I grew up.”

He adds: “Obviously a lot of people know about that, how I became very solitary.”

He describes this in his painfully-honest and excellent autobiography, “West By West,” detailing how he lost his brother, David, to the Korean War, along with family dysfunction that led to self-esteem issues he carried deep into adulthood. This created the craving for love that led to basketball.

“The most gratifying time for me was when I first picked up a basketball, shot it with these two hands, then for some reason the jump shot was easy. We had no car, so I was Forest Gump (and) ran everywhere all by myself for exercise, up and down the mountain. (I) then grew six inches one summer. To see what I’ve seen for 50-something years, well it’s been incredible.”

West received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2019, the highest civilian award. While West appreciated the gesture by former president Donald Trump, he is not a fan of that administration and the mood it produced.

“A country divided is not a good thing,” West says.

Love and respect. West has finally arrived at a comfort zone in his eternal search for both. He’s still devoted to his wife Karen, thrilled to see two of his sons, Ryan and Jonnie, as executives in the game, and joyous being a grandfather, most recently to the first child of Jonnie and pro golfer Michelle Wie.

Eight decades mostly tied to basketball brings a lifetime of moments worthy of reflection. And here’s one that captures the essence of West and everything he craved:

In the 1969 Finals, the Lakers and Celtics went to a Game 7. An old Bill Russell was on his last legs and last game, and the heavily-favored Lakers, who never beat Boston for a title, finally had their chance. Balloons were prepared to fall from the ceiling of The Forum in L.A. West was a problem for Boston all series. He averaged 37.9 ppg in the series, made big plays, shook the storied dynasty to its weakened core and became the only player from a Finals-losing team named series MVP.

West scored 42 points with 13 rebounds and 12 assists on a bad left hamstring in Game 7 but the Celtics prevailed anyway on a lucky Don Nelson shot. At the buzzer, West was overcome with tremendous grief. He sobbed while the Celtics celebrated. Then he felt a tugging on his arm, someone reaching for a hug.

“Jerry,” Russell whispered, “I love you, man.”

* * *

Shaun Powell has covered the NBA for more than 25 years. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.