It was never easy to swipe the basketball from the master of the crossover dribble, a weapon he popularized and introduced to the mainstream and used to change the game forever. But back in the day — to be specific, a crucial day in his basketball life — Tim Hardaway and his precious ball were taken.

His father bought him a Wilson for Christmas, his very first ball, and the young boy — or “Tim Bug” as he was known — was too small to dribble it. So, he sat on it, like a hen does her eggs.

A lifetime bond was formed and nothing seemed purer.

Hardaway, however, was born and raised on the South Side of Chicago, a famously edgy hood of hard-working people like the Hardaways, and unfortunately a few crooks as well. A kid in these parts knows not to leave his bike alone for a minute, and the same street law applied for a ball so shiny and new that it still had all its pebbles.

Hardaway forgot that law one day. Some kids stole the ball and ran. And Hardaway ran after them.

No, not Tim. His mom. Gwen Hardaway gave chase, up the street, ‘round the corner, down the alley, scraping her legs in the process, blood dripping, blood boiling. And those kids never stood a chance against a determined woman, who must have had the foresight to know what the basketball would someday mean to her son.

She snatched it back. She marched home.

“Here,” she said, with a bounce pass.

And so, for a player who delivered 7,095 assists in his NBA lifetime, this was the greatest assist given to him. Because, just maybe, if those delinquents had gotten away with it, who knows, we might’ve been deprived of ever seeing one of the most devastating dribbles known to man, of seeing the most entertaining trio in basketball — Run-TMC y’all — and of seeing a point guard stare into the camera during a 1990s Nike commercial shoot and utter three ad-libbed words that captured his essence:

“I got skeeeills,” Tim Hardaway bragged.

“Cut!” yelled the director, Spike Lee. “Damn, we’re gonna keep that. Man, that was great!”

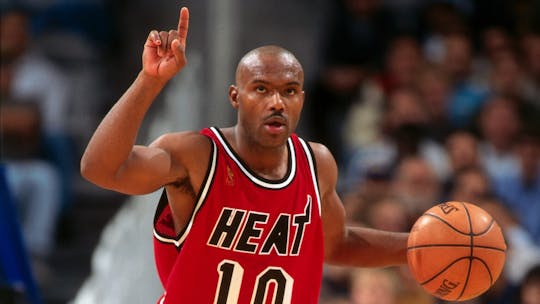

Tim Hardaway is now ready for induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Hardaway played primarily for Don Haskins, Don Nelson and Pat Riley, three coaches already in the Hall. He spent a ton of his minutes alongside Hall of Famers Mitch Richmond, Chris Mullin and Alonzo Mourning. Hardaway made those coaches smarter and those players better, so he’ll be immortalized next to them.

“He’s got the most confidence I’ve ever seen,” Mullin said.

He was barely 6 feet tall and not gifted with supreme athleticism. That was the extent of his limitations, though. Even his knuckleball jump shot was efficiently workable. Hardaway was a quick-reflex defender, directed his teams with unflinching leadership and served as a primary scoring option in an age where point guards were pass-first.

He was a showman for the Golden State Warriors for six seasons, then a leather-tough cornerstone in Miami with the hardscrabble Heat for six more. He made five All-Star and All-NBA teams and won a gold medal with the 2000 U.S. Olympic Team.

Raised on Chicago basketball, where the meek are left standing when sides are chosen in pickup games, Hardaway made his way to Texas-El Paso for college. Haskins — who coached the school formerly known as Texas Western to the historic 1966 championship over all-white Kentucky, inspiring the film “Glory Road” — was raging after UTEP suffered a season-opening 29-point loss to Washington in Hardaway’s first college game.

Haskins put the team through a two-hour workout once the wheels hit the runway back in El Paso.

“We just ran sprints and did defensive drills,” Hardaway recalled. “We didn’t touch the ball. So, after the workout, me and another player stuck around and played a little to stay sharp.”

In those one-on-one contests, Hardaway switched hands between dribbles, went between his legs, left his confused defender stuck to the floor, blew by him and dunked. There were no other witnesses in the empty gym for this landmark moment in basketball history, or so they thought.

“Wooo, damn!” said a school custodian, standing nearby in the hallway with a broom.

Hardaway did it again, this time faking a jumper before going strong to the rim for a layup. “That crossover is deadly,” the custodian gushed.

There was a player from the 1970s named Archie Clark, a former four-time All-Star who lasted 10 NBA seasons and mastered what was nicknamed “the Shake and Bake,” where he went left while his defender leaned right, and vice versa. And then a variation was adopted a decade later by the late Pearl Washington, who took the tricky dribble from the Brooklyn schoolyard to Syracuse and briefly the NBA.

Neither dribble-drive move was as effective, or jaw-dropping, or ankle-breaking, or show-stopping and certainly not as inspiring as the “killer crossover” created and owned by Hardaway. Stephen Curry is rightly applauded for changing the game with his 3-point shooting, Julius Erving with his dunking and Magic Johnson with his no-look passing.

Hardaway influenced the way the next generation dribbled. The crossover became his signature move after that day at UTEP — it was known during is college days as the “UTEP two-step” — and not only did it punch his ticket to NBA fame and ultimately the Hall, but it was also sewn into the fabric of the game. It was adopted by Allen Iverson, Jamal Crawford, Kyrie Irving and other greats. It’s now taught at the grassroots level.

Rarely is a game finished without someone crossing up someone else. The ultimate nightmare for any player is getting crossed, falling and then getting clowned from the bleachers.

And how does Hardaway react when he surveys all he created?

“I love it,” he said.

He does mention his crossover was fairly distinguished from others, how he froze defenders by going through his legs and how his imitators palm the ball by reaching underneath it. Hardaway frowned upon doing so and never resorted to such illegalities. Once defenders became wise to his crossover, Hardaway used variations (behind the back, head and/or shoulder fake) to stump them again and keep them frozen in place.

“A lot of people don’t recognize my signature crossover because it comes so fast,” he said. “You got to get low. If you know how to do it and stay low with it, it’s effective every time.”

Hardaway needed a weapon to create space between him and his defender because he was short and lacked speed, which became problematic when his knee was injured midway through his career. Hardaway managed to recover and return just as deceptive.

The Warriors drafted him at No. 14 in 1989 and Nelson hatched a plan. Nelson was one of the game’s great innovators and years earlier while coaching in Milwaukee, he created the “point forward” position by letting Paul Pressey, the Bucks’ small forward, handle the ball and create plays.

With the Warriors, Nelson created “small ball” somewhat out of necessity as the Warriors lacked a functional big man at that time. So, he formed his core around Hardaway, Richmond and Mullin, two guards and a small forward. Borrowing their nickname from one of rap’s biggest acts, Run-TMC (T for Tim, M for Mitch, C for Chris) was a matchup nightmare for teams and became a box office trio, averaging roughly 70 points nightly at their peak by scoring a variety of ways.

“Nellie devised a system where we could get up and down the floor and pass and entertain,” Hardaway said. “He knew if he gave me the keys, I could drive the car and do it the right way. With Chris and Mitch, it was easy.”

Nelson said: “Tim didn’t take long. He listened and became a leader when I challenged him to take that role.”

The Run-TMC Warriors were fun … but didn’t win. The show lasted just 164 games, going 81-83, which is a trivia answer now. Nelson traded Richmond for Billy Owens, drafted Latrell Sprewell, then swung a draft-day deal for Chris Webber.

With Owens, Mullin, Spree, C-Webb and Hardaway, they were poised to win. However, those plans never manifested as Hardaway was sidelined for the 1993-94 season due to a left knee injury he suffered in practice.

Hardaway, by then, was among the elites at his position. He was named to start the 1992 All-Star Game but surrendered that honor to Magic Johnson, who had recently retired after contracting the HIV virus. “It was the right thing to do,” Hardaway says today.

So not only did the Warriors have to make do without a star who averaged 20.6 points and 9.7 assists per game in his first four seasons, his leadership was missed as well. A rift developed between Webber and Nelson that festered, and the ensuing Webber trade ruined the ‘90s Warriors as the franchise didn’t truly begin to recover until Curry was drafted in 2009.

“I wasn’t around much and that really hurt us,” Hardaway said. “I could’ve talked to the guys and made them understand what (Nelson)was doing and also make Nellie understand the players, especially (Webber). I think I could’ve been a buffer and talked to both parties and we’d been alright.”

Hardaway himself was put on the block two years later when he appeared to lose a step. He placed a call to the leader of a team he thought needed him the most: Mourning and the Heat.

Hardaway said: “I told ‘Zo, `Trade for me (and) I’ll get y’all to the playoffs.’ I come from a head strong city in Chicago. I went to Miami and did what I was supposed to do, understood what Riley wanted, and we took off. We needed each other. Riley needed me and I needed him.

“He really wanted Gary Payton. But Gary didn’t want to come to Miami because he knew they practiced all the time. I knew Gary wasn’t coming, and I knew what I could do for Miami.”

(Payton did eventually migrate to Miami, years later in 2005, where he won his only NBA title.)

Oh, and the step that Hardaway lost? Regained. He averaged 19.1 ppg and 8.7 apg in his first three full seasons with Miami (1996-99) and, with Mourning, personified the toughness Riley preached for the club. The Heat engaged in a handful of testy fights with the New York Knicks in the playoffs, where the scores were low and tempers ran high. The atmosphere was made for a South Sider like Hardaway.

His personal Mona Lisa was Game 7 against the Knicks in the 1997 Eastern Conference semifinals. Mourning fell into late foul trouble and Hardaway stepped forward. He finished with 38 points, including six 3-pointers, and Miami advanced.

“I got to revert back to my old days, to taking over like I did in high school and college,” he said. “I focused my mind on that because Pat was pissed at Zo for getting that fifth foul and we had six minutes left in third quarter. So, I just went out and started making shots, making plays and making things happen.”

Like many other stars in his era, Hardaway could never crack the Michael Jordan code and reach the NBA Finals, much less win a championship. Still: He averaged 17.7 ppg, 8.2 apg and 1.6 spg in a 14-year career. Plus, his trademark crossover dribble outlasted him as even Curry believes it’s the best signature move ever.

Asking him to choose between the Warriors and Heat is asking him to choose between his son, Tim Jr. (an NBA player himself, now with the Mavericks) and his daughter, Nina.

“I identify with both teams,” he said. “I’ll tell y’all something. I had six great years with the Warriors, six with the Heat. It’s hard for me to differentiate and compare. Had great teammates with the Warriors and great teammates with the Heat. Had Hall of Fame coaches at both places. I can’t choose one over the other.”

His basketball idol was close to home, and Hardaway will never forget seeing him in person.

“Isiah Thomas is from Chicago,” Hardaway said. “Me and my youth coach went to see Isiah play. My coach said to watch No. 11, said I play a little like him, said I got the charisma he has and played with the confidence he had. I’m like, `get out of here. I’m in sixth grade.’ But I patterned my game after him ever since.”

And now Hardaway will have a place under the same roof as Thomas. (Thomas — as well as Richmond, Mullin, Yolanda Griffith and Nate Archibald — will serve as Hardaway’s presenters at the enshrinement ceremony.)

Hardaway is Hall-bound and he knows why: “I just had a lot of handles and I worked on my handles because I was short and needed to get around people. When we grew up, the game was physical, they could put their hand on you and steer you this way and that way. I could always dribble and avoid that. It was my ticket to basketball.”

Ticket punched … to Springfield.

* * *

Shaun Powell has covered the NBA for more than 25 years. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.